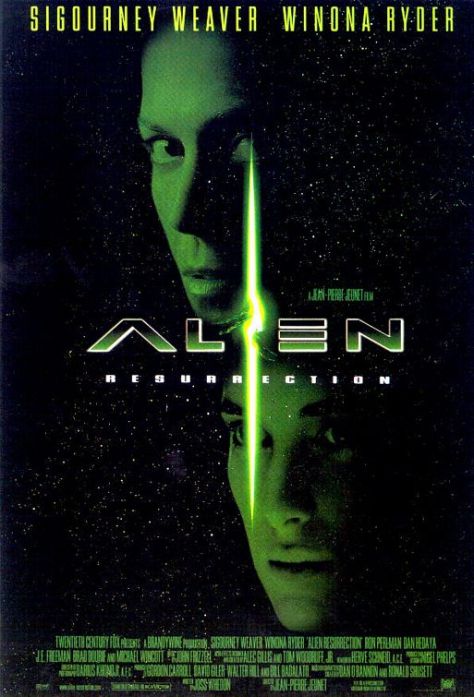

“Jeunet’s film thus finds a way of grafting two apparently opposed

or contradictory modes of reproduction onto one another. Cloning

suggests replication, qualitative indistinguishability, whereas

hybridity suggests the cultivation of difference, a new creation. In

Alien Resurrection, cloning engenders hybridity; even genetic replication

cannot suppress nature’s capacity for self-transformation and selfovercoming,

its evolutionary impulse. This film does not, then,

overcome Alien3’s attempted closure of the Alien series by resurrecting

either Ripley or her alien other – as if continuing (by contesting) David Fincher’s theological understanding of the alien universe;

for (as Thomas’ sceptical probing of Jesus’ resurrected body implies)

the religious idea of resurrection incorporates precisely the bodily

continuity that cloning cannot provide. The title of Jeunet’s film

thus refers not to a resurrection of the alien species, or of that

species’ most intimate enemy; it rather characterizes its hybrid of

cloning and hybridity as an alien kind or species of resurrection –

as something uncannily other to any familiar religious idea of

death’s overcoming.”

Stephen Mulhall, On Film